Thaton Moe Kyoe, the King of Lethwei

Thaton Moe Kyoe (left) and Yangon Aung Din meeting in a flag tournament final February 5th, 1980. ©Zoran Rebac.

Myanmar Traditional Boxing has always had its champions, most of them regional or territorial. But in the 70’s this was about to undergo a gradual change towards having a national champion, paired with a change in how the fights were fought.

The current lethwei rule-set has three-minute rounds for five rounds in total, and a 2 minute rest period in between rounds for most of the first and second class matches. There is also a timeout option and the fight may end in a draw. But why? To get the answers we need to go back 50 years. It all started when the King of Lethwei, Thaton Moe Kyoe, was in his prime.

The King of Punches

Moe Kyoe was born on November 6th, 1947 in Kyon Paik village, Hpa-An Township in Karen State. Some people might notice this was shortly after the execution of Major General Aung San in July, and just before Burma’s independence on January 4th of the following year. Because the situation in Karen state was characterized by frequent armed conflicts in the 1950’s, Moe Kyoe and his family fled to the Mon State border. His father who was a boxer in British colonial time, stayed behind and was killed.

Especially at that time the Thaton area was very active, and an abundance of pagoda festivals, donation festivals and monks funerals played host to boxing matches. Since it was only a few miles from where Moe Kyoe stayed with his family he was quickly introduced to the wonderful world that is traditional boxing. Unable to suppress his love and excitement for these fighting events he sought to participate in them as soon as possible. His brother Ko Maung Aye, who was a boxer himself, would go on to train Moe Kyoe.

After a few years, in the mid to late-60’s, Moe Kyoe (under the name Mot Htot) participated at an event in Kyaikto about 50 miles from Thaton. The event also played host to the circus of U Maung Maung and Arzarni San San who came to see the fights on their off-hours. When one of the ringside judges heard the members of the circus saying Moe Kyoe looked fast like a thunderbolt (Moe Kyoe in Burmese), he decided to start announcing him as such from that moment on. It was here where the name Thaton Moe Kyoe came to be.

The official title “King of Lethwei” (literally Boxing King) was appointed later. Moe Kyoe had already captured every first class flag by age 25 and up until 1977 had reportedly only lost twice. In 1980 Moe Kyoe briefly quit boxing due to a lack of opponents (and perhaps events) and started importing goods illegally for a few years to earn a living. He came back to boxing in the mid-to-late 80’s and eventually had one of his last fight against Shwe War Tun around 1991.

It is sometimes said that Moe Kyoe was undefeated for 12 years. But after closer inspection it seems to me that he was active in his professional career for 12 years. There are various printed media that state his 12 year long career, some with detailed fight history that include losses to Thaton Ko Gyi, Thaton Ba Hnit and Tha Mann Kyar. In fact one of the first fights in the new system, which will be described below, was a loss against Thaton Ba Hnit.

Problem & Solution

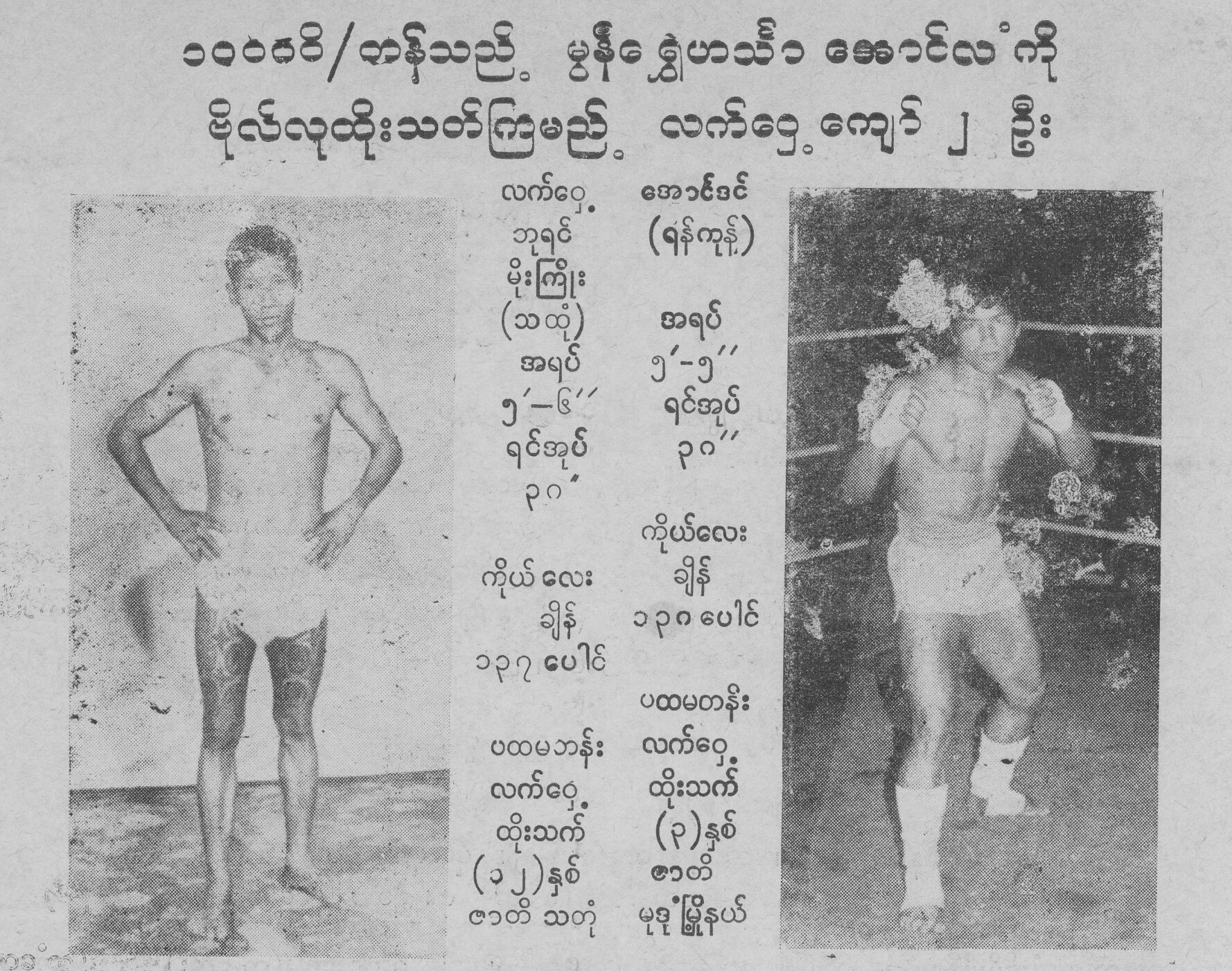

“Boxing King” Thaton Moe Kyoe

Image appears in a 1973 publication

Prior to the 1970’s most of the important fights were fought as flag fights. A tournament setting in which a competitor fought to eventually earn a flag in the finals in one of the skill classes, usually ranging from first to fourth, and sometimes with a 5th and also a ‘special’ flag.

These were the efforts of Kyar Ba Nyein, who you’ll have briefly read about in the introduction piece on this site. Where at first there was no system in how lethwei was practiced, he made the changes and presented a new solid foundation on which the sport still rides it’s coattails. A side-note to remember is that matches were fought bare fist without wraps, a tradition that also gradually changed in the 60’s.

In his time as a flag champion Moe Kyoe was a big attraction and promoters could cash in by having him on the bill. The tournaments that were set up to feature him started to have a problem when every participant started out saving their energy for an eventual meeting with Moe Kyoe at some stage in the tournament. Because he did not have that privilege since everybody was out to beat him, and had to literally fight for every punch and kick in each of the matches, it was considered unfair to Moe Kyoe.

The trio of Saya Kyar Ba Nyein (chief secretary of Myanmar Traditional Boxing at the time), Thaton Moe Kyoe and Saya U Bo Sein then decided that perhaps the western style of boxing might have the answer to their problem, and suggested to implement a rounds system (later referred to as the challenge fight system or new system).

Instead of having a flag tournament they eventually wanted to have the boxers prepare in advance and meet in the ring for a single challenge fight.

This change introduced a lot of new interesting challenges and ideas. First of all they had to determine the length of the matches, so they asked Moe Kyoe how long he would be able to survive in a single fight that had 3 minute rounds and 3 minutes rest in between the rounds. He answered it would probably be 20 rounds based on his experience and endurance, but they eventually settled on 15 to keep it fairer for the other competitors.

The flag tournaments did not disappear. For the time being both systems were used at the same time. Most of the people involved with the planning and decision making surrounding the new system all agreed that if it didn’t work out, it would be abandoned and they’d stick with the traditional system only.

Timeout, Draw & Decision

The original flag fights not only had rest periods in between rounds, but also within each round. A total of three ‘Lar’ were incorporated into each round where the referees took it upon themselves to take care of the two boxers by way of stretching and massaging them, or reassuring them and making sure they were comfortable to continue. This particular feature was missing from the new system and they feared that if there wasn’t any rest period like this, the fights may end way too quickly and the audience would not be satisfied. This is where the timeout is born. However, this timeout was only implemented to keep the audience happy. Most of the fights went on for a long time and since the ticket prices didn’t change with the coming of the new system, they needed a way to warrant the prices by keeping the audience satisfied. We know now that the meaning of the timeout has slightly shifted to “benefit” a knocked out or hurt boxer instead of the audience.

The initial suggestion was a single five-minute resting period which was discussed and changed and eventually changed again by Kyar Ba Nyein to be two six-minute timeouts in a single 15 round match.

Flag fights initially had no end to them, unless one boxer gave up, was cut or could not continue after three challenges in the last round. They were also known as ‘killing battles’.

With the new finite 15 round system in place there needed to be a solution for the end of the fight. When asked, most of the audience members agreed that a match was satisfactory by default if it had reached the last rounds so Kyar Ba Nyein, U Bo Sein et al. decided upon the draw, perhaps borrowing it from the way matches ended in the Thai border regions when boxers met for Burma vs. Thailand challenges. Moe Kyoe had gone there (to Myawaddy) as a third class boxer to challenge Thai fighters himself around 1966.

They would introduce a marking system for the judges at ringside only if there was an official challenge to the top boxer in the region, to make succession possible.

The Champion

U Pyinnyar Sar Ya—Moe Kyoe

Moe Kyoe entered monkhood in 1998 at the age of 52. He is known as U Pyinnyar Sar Ya.

Prior to the changes made by Kyar Ba Nyein in the 1950’s there were no clear champions, especially in the form of a flag champion or national champion like we do now. Perhaps a decent analogy can be made by comparing it to regional and indie pro-wrestling where promotions held territories and superstars were borrowed to match with a superstar from a different territory. This was largely the same for lethwei. A lot of the boxers built up their reputation in a town or township. Particularly at the time of Moe Kyoe many carried the name of their stomping ground or hometown, hence the name “Thaton” Moe Kyoe, which in some ways created a sense of rivalry in their matches.

With the advent of the flag tournaments with the efforts of Kyar Ba Nyein, the champions were crowned in each class. So the first, second and third-class flag champions could be considered on par with a national champion as we know them today. Even more so when they won multiple flags. The gradual change towards having a national champion started with the rivalry of Moe Kyoe and Tha Mann Kyar. Because Tha Mann Kyar didn’t start his pro career until around 1976 he basically came into the sport with the new system already in place where the focus had been taken away from the flag tournaments.

I cannot pinpoint where, when and who appointed a boxer as Burmese champion, but the fact that the current Myanmar Traditional Boxing Federation recognizes Tha Mann Kyar as the first Burmese champion says enough.

So even though Moe Kyoe and Tha Mann Kyar do not share the same title, they certainly share the same status. It just had a different name. The specifics of some of the fights between the two will be discussed in the Tha Mann Kyar article forthcoming.

“We didn’t know technique but tried very hard to win all fights. All the guys and senior boxers in the ring were our teachers. A high fighting spirit was the most important. It was a desire. A desire to win, that’s all.”

Header is part of a two-sided pamphlet voluntarily donated by Zoran Rebac for exclusive use by The Fight Site and Myanmar Lethwei Collection. The original material that was used for this article is sourced from interviews with Moe Kyoe, Tha Mann Kyar and the late Saya U Bo Sein, thanks to the efforts of U Oscar and Zin Lin Tun. Special thanks to Phyu Zin Thant, Min Oakar and Saw Myo Min Hlaing for their assistance.